The Yarf! reviews by Fred Patten

Note: This is a fraction of the entire listing. If you’re on broadband, you might want to try the high speed version instead.

The Yarf! reviews by Fred Patten

Note: This is a fraction of the entire listing. If you’re on broadband, you might want to try the high speed version instead.

Welcome to the “Patten’s reviews” wing of the Anthro Library! Since this is a collection of columns from a dormant (if not dead) furzine called YARF!, a word of explanation might be helpful: In its day, YARF! (aka ‘The Journal of Applied Anthropomorphics’) was perhaps the best-known—and best in quality—of furry zines. Started in 1990 by Jeff Ferris, YARF!’s roster of contributors reads like a Who’s Who of furdom in the last decade of the 20th Century. In any issue, the zine’s readers could expect to enjoy work by the likes of Monika Livingstone, Watts Martin, Ken Pick, and Terrie Smith; furry comic strips such as Mark Stanley’s Freefall… and Fred Patten’s reviews of furry books and comics.

Unfortunately, YARF! has been thoroughly inactive since its 69th issue, which was released in September 2003. We can’t say whether YARF! will ever rise again… but at least we can prevent its reviews from falling into disremembered oblivion. And so, with the active cooperation of Mr. Patten, Anthro is proud to present Mr. Patten’s review columns—including the final one, which would have appeared in the never-printed YARF! #70.

Full disclosure: For each reviewed item, we’ve provided links you can use to check which of four different online booksellers—Amazon.com

, Barnes & Noble

, Alibris

, and Powell’s Bookstore—now has it in stock. Presuming the item in question is available, if you buy it Anthro gets a small percentage of the price.

#49 / Jul 1997 |

||||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

||

| Title: | Pig Tales: A Novel of Lust and Transformation | |

| Author: | Marie Darrieussecq | |

| Translator: | Linda Coverdale | |

| Publisher: |

The New Press (New York, NY), May 1997 |

|

| ISBN: | 1-56584-361-4 | |

|

151 pages, $18.00 |

||

| Availability: | Am |

|

The unnamed narrator tells on the first page how difficult it is to write her manuscript, now that she is a big pig without hands, wallowing in the mud. The story is her rambling reminiscences, in excruciating detail, about her feminine problems as she gradually transformed into an obese, multi-dugged, corkscrew-tailed sow.

This opening is important, since the story takes quite a while to reach that point. It starts with the narrator’s pride when she became the top beautician at Perfumes Plus, a tres chic beauty/health salon. It is quickly obvious what this boutique really was, since her main duty was screwing anything (of both sexes) more animate than the furniture, with offhand references to her bosses paying off the vice squads by giving them free privileges. Naturally, her status as Perfumes Plus’ premiere beauty suffered as she started to bulge and rip her tight dresses, her hair turned to stiff bristles, she grew extra teats, and so on (even though a growing number of customers didn’t mind, as their tastes were swinging toward animal-style sex). Her emphasis in this first part is on her frantic use of the boutique’s beauty aids in an attempt to keep her good looks; her worries that changes in her menstrual routine meant that she had become pregnant—or sterile—or had cancer (she belatedly realized that it was due to her shift from human to porcine femininity); how her rivals among the female staff plotted her downfall; and her despair over the growing disgust of her sophisticated lover, Honoré, towards her.

Inevitably, she was thrown out on the streets and became a bag lady. This was not too bad, since she didn’t mind the cold due to her thickened hide, nor did she find eating garbage offensive any more. But the focus remains on her personal affairs. There are only frustratingly vague glimpses of the increasingly chaotic political situation: the right-wing expulsion of all foreigners from France; a new Reign of Terror; replacing the Arc de Triomphe with a cathedral; a counterrevolution; the extremist government’s conversion of the SPCA into a super-Gestapo. This may have had something to do with the animalization of humanity, but the narrator didn’t really care. “There was a lot of talk about Edgar’s [the fascist political leader] mental illness. It seems he was neighing and eating nothing but grass, down on all fours. Poor Edgar.” (pg. 114) “The director was extraordinarily handsome, even more so than Honoré. He sniffed my rear end instead of shaking my hand, but aside from that he couldn’t have been nicer, a truly refined man, well dressed and everything.” (pg. 115)

For ’morph fans, the crux of the novel is her meeting with Yvan and becoming his mistress. Yvan had become a wolf, and was proud of it. He had learned to shift back and forth between his human and animal states by willpower, and he taught her the advantages of both existences. “Yvan loved me equally well as a woman and as a sow. He said it was fantastic to have two modes of being, two females for the price of one, in a way, and what a time we had.” (pg. 122) They could have it as human-human, human-pig, human-wolf, or wolf-pig. Yvan also taught her that one could be a sow and still be elegant. He got her a jeweled collar and leash, and took her out promenading around the boulevards, as an aristocratic socialite with his pet blue-ribbon pig. Unfortunately, this was only a tragically brief interlude. Without Yvan’s strong personality to support her, the narrator sank back into her increasingly squalid swinish existence.

With Pig Tales’ concentration and obsession on kinky sex—including lurid scenes of the highest government officials’ secret torture/snuff orgy nests—it is probably no wonder that this 27-year-old schoolteacher’s first novel became France’s publishing sensation of 1996. (The French title, Truismes, is a pun on ‘truisms’ and ‘truie’, the French word for ‘sow’. Curiously, the nameless narrator has a name in the French edition: Zoé.) It skyrocketed to the top of the best-seller charts as soon as it reached the bookshops. According to Livres Hebdo #217, 20 Sept. 1996, pg. 47, “The print run of the book swelled from 4,000 copies on 28 August [its release date] to 55,000 copies on 17 September!” By the end of 1996 there were 173,000 copies in print, with sales passing over 3,000 copies a day at its peak. It became a finalist for France’s literary Prix Goncourt, and a major movie directed by Jean-Luc Godard is in production.

The novel’s reception in America is problematical, and its appeal to ’morph fans is even more so. This first-person flashback is overwhelmingly permeated with the narrator’s shallowness, which would seem a major irritation. The story is totally self-centered on a basically boring person. It becomes imaginative only as her viewpoint shifts from human to porcine. There are some intriguing descriptions of her emotional turmoil during the transformation of her feelings and instincts. But this is over halfway through the novel, which may make it too little and too late for some readers. Also, most of the detailed descriptions are of human lusts. The references to doing it doggy (or piggy or horsey…) style are very brief, as though she assumes that the human readers for whom she is writing her memoirs would not be interested in this.

However, the French critics seem to feel that this is one of the points which makes Pig Tales such a devastating satire. It reveals the unimportance of world events in comparison to one’s banal personal concerns. So it is only natural that the comments about France’s political collapse (with machine-gun-toting SPCA terror squads ruling the streets) are brief and annoyingly cryptic, while the narrator goes into pages of detail about what she wore and what makeup she used and how hard she tried to please her lover of the moment; with as many piggy-wiggy puns as possible. Well, chacun à son goût. The French love Jerry Lewis, too. ![]()

|

||

| Title: | Empire of the Ants | |

| Author: | Bernard Werber | |

| Translator: | Margaret Rocques | |

|

|

||

| Publisher: |

Bantam UK (London, UK), Mar 1996 |

|

| ISBN: | 0-593-03385-X | |

|

Hardcover, 275 pages, £9.99 |

||

| Availability: | Am |

|

|

|

||

| Publisher: |

Corgi Books (London, UK), Jan 1997 |

|

| ISBN: | 0-552-14112-7 | |

|

Paperback, 348 pages, £5.99 |

||

| Availability: | Am |

|

In the early days of the s-f pulp magazines, there was a vogue for ‘scientific fiction’ as sugar-coated scholasticism. Many of these worked nicely at awakening ‘the sense of wonder’ in adolescent readers, although anyone who went on to actually study astronomy or zoology or biology soon realized that they were much too anthropomorphized (or geomorphized) to be accurate as scientific education. Most were too didactic to be worth much as fiction, either.

(For an example appropriate to this review, read Clifton B. Kruse’s Dr. Lu-Mie (Astounding Stories, July 1934). The human narrator is kidnapped into a termitarium by Lu-Mie, a termite ‘scientist ’. The story is mostly an educational travelogue of the daily routine in a termite nest, as observed by the narrator as Lu-Mie boastfully shows him around, and as he flees through its corridors trying to escape.)

Science fiction has advanced considerably in the last sixty years. Bernard Werber’s Empire of the Ants (originally published in France in 1991 as Les Fourmis, from Albin Michel) is excellent both as an intriguing two-pronged mystery novel, and as a basically accurate depiction of life among different species of ants despite their anthropomorphization.

The initial protagonist of the human mystery is Jonathan Wells, a young husband who has recently lost his job. So it is a godsend when his scientist Uncle Edmond dies and he inherits Edmond’s house in the Fontainebleau forest district of Paris. This is an upper-middle-class neighborhood of residences and nearly woodlands, where the well-maintained houses are several centuries old. Edmond’s house seems normal except for the locked cellar door and the note, ‘ABOVE ALL, NEVER GO DOWN INTO THE CELLAR!’ Since Jonathan has a ten-year-old son and a yappy poodle, you can imagine for how long that admonition is observed.

Six kilometers away, in the forest, is the russet ant metropolis of Bel-o-kan, home to 18 million inhabitants. Its story starts by following a young ant, the 327th male of the current breeding season. The introductory scenes among the ants are of a travelogue nature until 327th joins an expedition of 28 other ants to bring in some carrion from the forest. 327th falls slightly behind the others on the trail; when he catches up to them, they are all dead without a mark upon them. 327th rushes home to warn Bel-o-kan of a danger, as ants are supposed to do, even though he does not know what killed them:

Ants came running from all directions.

He’s talking about a new weapon and an expedition that’s been decimated.

It’s serious.

Can he prove it?

The male was now at the centre of a knot of ants.

To arms, to arms! War has been declared. Clear for action!

Can he prove it?

They all started repeating the scent question.

No, he could not prove it. He had been in such a state of shock that he had not thought of bringing anything back with him. Antennae stirred. Heads moved doubtfully. (pg. 50, Corgi ed.)

Since 327th cannot prove there is a danger, the ants soon ignore him and return to their regular duties. Neuter worker ants are more regimented and less imaginative than males, and the ant city is just awakening after a winter’s hibernation so there is much to do.

In the Tribe, decisions were made by constant consultation, through the formation of working parties which chose their own projects. If he wasn’t capable of generating one of these nerve centres—in short of forming a group—his experience was useless. (pg. 56)

327th decides to form a small group, to convince a few ants to follow him and see the bodies of the dead expedition. Their verification will be enough to convince the city that there is a real danger to mobilize against; to identify the unknown enemy and to prepare a defense against it. However, 327th has hardly begun when he narrowly escapes being murdered by ants within Bel-o-kan itself. This is unheard of! Different species of ants have different modes of fighting, and the russet ants have been warring with a city of dwarf ants who have recently migrated into their forest. But the species are so distinct that no ant has ever been able to disguise itself successfully enough to enter another’s city; nor are ants individualistic enough for any to be persuaded to betray their own cities. And ants do not attack each other within their own Tribes. So who is trying to kill 327th? And why?

The two stories are interwoven, although there are about three chapters of the ant mystery for each chapter of the human mystery. Both are intriguing, with unexpected surprises. But they are so separate that they might be two entirely different novels. Jonathan’s cellar turns out to be a dark stairway that goes down and down—and down—and down—until his story seems about to turn into a Lovecraft pastiche, with hideous squeaks echoing from abysmal depths:

“It’s incredible. What were you doing down there for eight hours? What’s at the bottom of that damn cellar?” she [his wife] flared.

“I don’t know what’s at the bottom. I didn’t get there.”

“You didn’t get to the bottom?”

“No, it’s very, very deep.”

“You didn’t get to the bottom of… of our cellar in eight hours?” (pg. 66)

The story of 327th, and the two comrades he finally enlists to solve the ant mystery—the 56th female (a ‘princess’ who will soon leave Bel-o-kan with other young females to start new cities) and the 103,683rd soldier, an old neuter warrior/guard—is exciting. But it seems to be a realistic adventure of warfare among the ant nests of a Northwestern European forest, battles against other natural predators of ants such as woodpeckers and moles, and the fictitious puzzle of identifying the enemy among their own fellow russet ants. There appears to be no possible connection, except that there are constant hints that Jonathan’s scientist uncle, who left the warning to never enter the cellar, was conducting experiments on ants.

I don’t want to spoil this book by revealing too much, but I will warn that it ends on a cliffhanger—though not the cliffhanger that the reader is led to expect. The sequel, Le Jour de Fourmis, has already been published in France. Empire of the Ants itself is scheduled for an American edition, under a straight translation of the French title—The Ants—from Bantam Books this December. Most of the mysteries in this first volume are answered, although some of the answers—especially in the human mystery—are more Hollywood-dramatic than convincing. (People who know there are monsters around will wander off alone into the darkness…) But the emphasis of the novel is a murder mystery among ants which manages to simultaneously keep the ants natural enough to be ‘seriously educational’, and anthropomorphized enough to stand out as individuals. Making realistic ants sympathetic enough for the reader to care about them is a good enough trick that Empire of the Ants is worth reading for that alone. ![]()

2007 Note: This is actually the first novel of a trilogy in France. The three are Les Fourmis (Albin Michel, March 1991; 351 pages), Le Jour des fourmis (Albin Michel, November 1992; 463 pages), and La Révolution des fourmis (Albin Michel, May 1996; 533 pages). There is also an omnibus edition, La Trilogie des fourmis (Le Livre de Poche, January 2004; 1393 pages). Only this first volume has been published in English so far.

#50 / Sep 1997 |

||||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

||

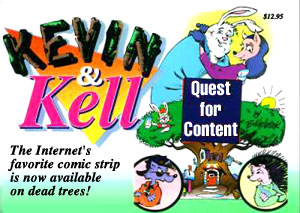

| Title: | Kevin & Kell: Quest for Content | |

| Creator: | Bill Holbrook | |

| Publisher: |

Online Features Syndicate (Norcross, GA), May 1997 |

|

| ISBN: | — | |

|

138 pages, $9.95 |

||

| Availability: | Am |

|

This is the first collection of Bill Holbrook’s Kevin & Kell comic strip. Kevin & Kell’s main claim to fame is that it is the first daily strip created especially and exclusively for Internet publication, where it appears mostly on CompuServe forums. It is also one of the most imaginative funny-animal strips ever published anywhere, thanks to its clever usage of animal traits in a modern situation-comedy setting.

Kevin & Kell Dewclaw are a modern couple—though their mixed marriage is definitely not typical. Kevin (in his mid-thirties) is a rabbit, and Kell (in her late twenties) is a wolf. It is the second marriage for both of them. Kevin’s first marriage broke up when his militantly independent rabbit wife walked out on him, leaving him with their adopted daughter Lindesfarne (mid-teen), a porcupine. Kell’s first husband was killed trying to singlepawedly bring down a moose, leaving her with a young-teen cub, Rudy. Kevin & Kell met and developed a romance through an online discussion forum. By the time they finally realized that he was a herbivore and she was a carnivore, they were too much in love to break it off.

At the time Kevin & Kell begins, they have been married for a year and are expecting their own first child. Lindesfarne and Rudy are in the throes of teen step-sibling rivalry. Rudy loses no opportunity to remind her that he is a macho predator, while Lindesfarne loftily points out that, as a more mature porcupine, she is nobody’s prey. Kevin’s & Kell’s families have both disowned them in hostility over the mixed marriage, and Kevin’s inept brother-in-law Ralph keeps trying to eat him. Kevin works at home, as the sysop manager of the Herbivore Forum. Kell has an office job at Herd Thinners, Inc., a public-service corporation which helps manage population control.

Kevin & Kell: Quest for Content presents the first year of the strip, from September 4, 1995 to August 29, 1996. It contains 258 Monday-Friday daily strips (actually 257; the 12/13/95 strip is accidentally printed twice and the 12/14 strip is missing) and six monthly Sunday-format strips. The humor revolves around two major topics: computers, and ‘the law of the jungle’ as applied to modern American life.

Part of Kevin’s attraction for Kell was that she was tired of being pawed by the slavering, predatory males with whom she had previously associated. An early question is what the first child of their mixed marriage will be like. The child, Coney, is born two months into the strip; and how she affects their family is a continuing theme. Kevin’s status as a herbivore is useful for household chores (he doesn’t have to mow the lawn; he grazes it). Contrariwise, Kell finds her job at Herd Thinners harder since she has to work farther afield to avoid preying on any of Kevin’s family or friends. Rudy and Lindesfarne and their friends are focuses for teen and school-related humor. Rudy, as a wolf cub, tends to eat his own homework, both the paper variety and in field classes like Sneaking Up On Prey 101. He develops a puppy-love relationship with Fiona Fennec, and is crushed when she has to return with her parents to the MidEast. (But they stay in touch via the Internet, providing lots of jokes based on email romances.) Kevin listens to the online complaints of insects; their lifespan is so short that they’re dead before they can get tech support. Rudy is scolded for drinking out of the toilet. When Lindesfarne gets into an online argument, she doesn’t flame, she quills. Kevin has hardware problems because practically everyone in his household sheds. When Kevin is called away from home on a mysterious freelance assignment in early April, Rudy and Lindesfarne join forces to investigate whether he is really the Easter Bunny.

Kevin & Kell almost never merely places animal heads on human bodies. Virtually every joke depends on the animal natures of the characters: that they are carnivores or herbivores, or that they are color-blind or they shed. Despite this mixed cast, Holbrook has made the Dewclaws into a loving family that is more functional than many in today’s TV and comic-strip situation comedies.

Kevin & Kell is Bill Holbrook’s third comic strip. He has been writing & drawing On the Fastrack and Safe Havens, both with human casts, for the newspapers since the 1980s; he is currently producing all three simultaneously. As a result, Kevin & Kell does not show the rapid changes in art style which many beginning cartoonists’ strips go through during their first months. It has a professional consistency throughout.

Holbrook was a Guest-of-Honor at ConFurence VIII this past January. He announced that he was trying to sell a Kevin & Kell volume, but that so far no book publisher was interested because they only collected ‘newspaper comic strips’ and Kevin & Kell did not appear in newspapers. Holbrook apparently gave up, because this book is self-published. Kevin & Kell: Quest for Content is available for $9.95 + $1.75 shipping from Holbrook’s own Online Features Syndicate, P. O. Box 931264, Norcross, GA 30093. The book contains an advertisement for other Kevin & Kell merchandise such as T-shirts, screen savers, and mouse pads. ![]()

|

||

| Title: | Reinardus; Yearbook of the International Reynard Society | |

| Publisher: |

John Benjamins Publishing Company (Amsterdam), 1988-1997 |

|

| ISSN: | 0925-4757 | |

|

ca. 200-250 pp. each, Hfl. 117,– (v. 1-9), Hfl. 130,– (v. 10) |

||

| Availability: | Am / BN / Al / Pw | |

I would like to thank Michael Russell of Orlando for informing me about the International Reynard Society and its Yearbook. To quote from the Society’s literature, “The International Reynard Society was founded in 1975 by Professor Kenneth Varty of the University of Glasgow and the late Nico Van Den Boogaard of Amsterdam, to group together medievalists and other scholars in […] essentially, the associated fields of the so-called ‘Beast Epic’ of Reynard the Fox, the Fable tradition, and the short comic narrative genre exemplified by the Old French Fabliaux.” It has held an International Colloquium in Europe every two years since 1975 (Glasgow in 1975, Amsterdam in 1977, Münster in 1979, Paris in 1981, and so on), almost always at universities; a special out-of-sequence colloquium was held in Tokyo in July 1996.

Its Yearbook consists primarily of the publication of scholarly papers which have been read at these colloquiums. “Reinardus aims to promote comparative research in the fields of medieval comic, satirical, didactic, and allegorical literature, with emphasis on beast epic, fable and fabliau, including sources, influences and later developments into the modern period. The methods and critical interpretations it offers are as wide-ranging as is its subject matter, since it considers discussion and the coexistence of conflicting views as more important than the defence of a specific methodological point of view.”

Each volume consists of 15 to 25 papers in either English or French (and very occasionally Italian), usually about evenly divided. Despite the Society’s comment about “later developments into the modern world”, there are barely a handful of articles which touch on anything more recent than the 18th century. Some average titles are:

Most articles are unillustrated, but there are a couple in each volume which include plates showing Medieval or Renaissance woodcuts, photographs of humorous carvings in old churches, and the like.

Frankly, Reinardus seems too academically dull for the average ‘Furry fan’. However, it is an excellent source for information about all aspects of the Medieval Reynard the Fox fable and other talking-animal satires. The discussions of Reynard encompass profiles of the entire cast: King Nobel the lion, Isengrim the wolf, Bruin the bear, Tibault the cat, Baldwin the donkey, Chantecleer the rooster, Grimbert the badger, Belyn the ram, Cuwert the hare and many others who have faded into anonymous background roles in the streamlined modernizations. These essays also detail the brutal and adult nature of the original fable. In modern versions, Isengrim asks King Nobel to punish Reynard because the fox has ‘insulted’ him, which implies little more than that the wolf is haughty and not bright enough to think of witty comebacks. The unexpurgated tale specifies how the insult was that Reynard broke into the wolf’s home during his absence to rape his wife and blind his cubs, just to flaunt his power. The original texts quoted in Reinardus will be of interest to anyone wanting to compile notes on Medieval French and Dutch scatology, obscenities, and erotic scurrility.

Reinardus is also horrendously expensive. The current foreign exchange rate of the Dutch guilder is U.S. 50.8¢. This makes the first nine volumes approximately $60.00 apiece, and the current volume $66.00, not counting shipping. However, the cost is only U.S. $30.00 per volume to members of the International Reynard Society, and membership in the Society is free upon request. For membership information, inquire to the International Secretary, Dr. Brian J. Levy, Department of French, The University of Hull, Hull HU6 7RX, England, U.K.; or e.mail: b.j.levy@french.hull.ac.uk. For information about ordering Reinardus, the publisher’s North American address is: John Benjamins North America, P. O. Box 27519, Philadelphia, PA 19118-0519; (215) 836-1200; customer.services@benjamins.nl; http://www.benjamins.nl.

To digress, even if the Society and Reinardus are too scholarly for the tastes of most of our group, it seems incredible that apparently none of us (with the exception of Michael Russell) have even been aware of the existence of this international society of enthusiasts of talking-animal legends and stories, which has been holding conferences all around Europe (and in Japan) every two years since 1975, and publishing a thick annual collection of studies for the past decade. I have been active in ’morph fandom since the early 1980s, and I had never heard of such an organization during all this time. It makes one wonder what other anthropomorphisms may be out there that we don’t know about. ![]()

2007 Note: Reinardus is still being published; current ordering information is at http://www.benjamins.com/cgi-bin/t_seriesview.cgi?series=REIN. The latest issue seems to be vol. 18, 2005. I still have not heard a word in anthropomorphics fandom about it or the International Reynard Society to this day.

|

|